Photograph, framed: 100 x 65 inches (254 x 165.1 cm)

Text, framed: 69 x 56 1/8 inches (175.3 x 142.9 cm)

This installation size: 100 x 129 5/8 inches (254 x 329.2 cm)

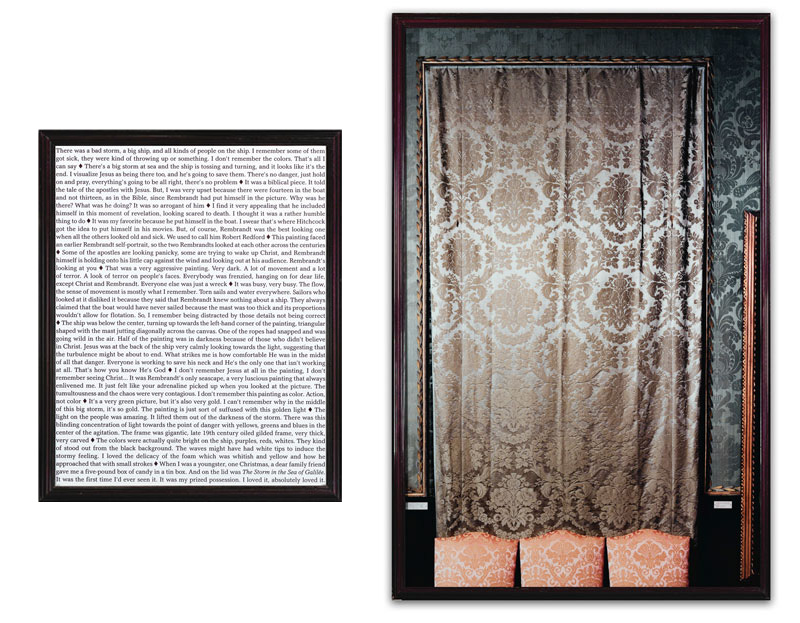

In her series Last Seen…, Sophie Calle creates a poetic remembrance of a famous crime: the theft in 1990 from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston of five drawings by Degas, a vase, a Napoleonic eagle, and six paintings by Rembrandt, Flinck, Manet, and Vermeer. Gardner’s stipulation in her will that the arrangement of the galleries remain fixed ensures that a sense of loss remains a permanent fixture of the museum. Calle interviewed curators, guards, and other staff members, asking them to describe the absent works; their varied responses are displayed as a counterpart to photographs of the labels, empty pedestals, and bare wall hooks left behind after the theft

The text reads:

There was a bad storm, a big ship, and all kinds of people on the ship. I remember some of them got sick, they were kind of throwing up or something. I don’t remember the colors. That’s all I can say ✦ There’s a big storm at sea and the ship is tossing and turning, and it looks like it’s the end. I visualize Jesus as being there too, and he’s going to save them. There’s no danger, just hold on and pray, everything’s going to be all right, there’s no problem ✦ It was a biblical piece. It told the tale of the apostles with Jesus. But, I was very upset because there were fourteen in the boat and not thirteen, as in the Bible, since Rembrandt had put himself in the picture. Why was he there? What was he doing? It was so arrogant of him ✦ I find it very appealing that he included himself in this moment of revelation, looking scared to death. I thought it was a rather humble thing to do ✦ It was my favorite because he put himself in the boat. I swear that’s where Hitchcock got the idea to put himself in his movies. But, of course, Rembrandt was the best looking one when all the others looked old and sick. We used to call him Robert Redford ✦ This painting faced an earlier Rembrandt self-portrait, so the two Rembrandts looked at each other across the centuries ✦ Some of the apostles are looking panicky, some are trying to wake up Christ, and Rembrandt himself is holding onto his little cap against the wind and looking out at his audience. Rembrandt’s looking at you ✦ That was a very aggressive painting. Very dark. A lot of movement and a lot of terror. A look of terror on people’s faces. Everybody was frenzied, hanging on for dear life, except Christ and Rembrandt. Everyone else was just a wreck ✦ It was busy, very busy. The flow, the sense of movement is mostly what I remember. Torn sails and water everywhere. Sailors who looked at it disliked it because they said that Rembrandt knew nothing about a ship. They always claimed that the boat would have never sailed because the mast was too thick and its proportions wouldn’t allow for floatation. So, I remember being distracted by those details not being correct ✦ The ship was below the center, turning up towards the left-hand corner of the painting, triangular shaped with the mast jutting diagonally across the canvas. One of the ropes had snapped and was going wild in the air. Half of the painting was in darkness because of those who didn’t believe in Christ. Jesus was at the back of the ship very calmly looking towards the light, suggesting that the turbulence might be about to end. What strikes me is how comfortable He was in the midst of all that danger. Everyone is working to save his neck and He’s the only one that isn’t working at all. That’s how you know He’s God ✦ I don’t remember Jesus at all in the painting, I don’t remember seeing Christ…It was Rembrandt’s only seascape, a very luscious painting that always enlivened me. It just felt like your adrenaline picked up when you looked at the picture. The tumultousness and the chaos were very contagious. I don’t remember this painting as color. Action, not color ✦ It’s a very green picture, but it’s also very gold. I can’t remember why in the middle of this big storm, it’s so gold. The painting is just sort of suffused with this golden light ✦ The light on the people was amazing. It lifted them out of the darkness of the storm. There was this blinding concentration of light towards the point of danger with yellows, greens and blues in the center of the agitation. The frame was gigantic, late 19th century oiled gilded frame, very thick, very carved ✦ The colors were actually quite bright on the ship, purples, reds, whites. They kind of stood out from the black background. The waves might have had white tips to induce the stormy feeling. i loved the delicacy of the foam which was whitish and yellow and how he approached that with small strokes ✦ When I was a youngster, one Christmas, a dear family friend gave me a five-pound box of candy in a tin box. And on the lid was The Storm in the Sea of Galilée. It was the first time I’d ever seen it. It was my prized possession. I loved it, absolutely loved it.

Edition 1 of 2

(Inventory #30284)

Photograph, framed: 100 x 65 inches (254 x 165.1 cm)

Text, framed: 69 x 56 1/8 inches (175.3 x 142.9 cm)

This installation size: 100 x 129 5/8 inches (254 x 329.2 cm)

In her series Last Seen…, Sophie Calle creates a poetic remembrance of a famous crime: the theft in 1990 from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston of five drawings by Degas, a vase, a Napoleonic eagle, and six paintings by Rembrandt, Flinck, Manet, and Vermeer. Gardner’s stipulation in her will that the arrangement of the galleries remain fixed ensures that a sense of loss remains a permanent fixture of the museum. Calle interviewed curators, guards, and other staff members, asking them to describe the absent works; their varied responses are displayed as a counterpart to photographs of the labels, empty pedestals, and bare wall hooks left behind after the theft

The text reads:

There was a bad storm, a big ship, and all kinds of people on the ship. I remember some of them got sick, they were kind of throwing up or something. I don’t remember the colors. That’s all I can say ✦ There’s a big storm at sea and the ship is tossing and turning, and it looks like it’s the end. I visualize Jesus as being there too, and he’s going to save them. There’s no danger, just hold on and pray, everything’s going to be all right, there’s no problem ✦ It was a biblical piece. It told the tale of the apostles with Jesus. But, I was very upset because there were fourteen in the boat and not thirteen, as in the Bible, since Rembrandt had put himself in the picture. Why was he there? What was he doing? It was so arrogant of him ✦ I find it very appealing that he included himself in this moment of revelation, looking scared to death. I thought it was a rather humble thing to do ✦ It was my favorite because he put himself in the boat. I swear that’s where Hitchcock got the idea to put himself in his movies. But, of course, Rembrandt was the best looking one when all the others looked old and sick. We used to call him Robert Redford ✦ This painting faced an earlier Rembrandt self-portrait, so the two Rembrandts looked at each other across the centuries ✦ Some of the apostles are looking panicky, some are trying to wake up Christ, and Rembrandt himself is holding onto his little cap against the wind and looking out at his audience. Rembrandt’s looking at you ✦ That was a very aggressive painting. Very dark. A lot of movement and a lot of terror. A look of terror on people’s faces. Everybody was frenzied, hanging on for dear life, except Christ and Rembrandt. Everyone else was just a wreck ✦ It was busy, very busy. The flow, the sense of movement is mostly what I remember. Torn sails and water everywhere. Sailors who looked at it disliked it because they said that Rembrandt knew nothing about a ship. They always claimed that the boat would have never sailed because the mast was too thick and its proportions wouldn’t allow for floatation. So, I remember being distracted by those details not being correct ✦ The ship was below the center, turning up towards the left-hand corner of the painting, triangular shaped with the mast jutting diagonally across the canvas. One of the ropes had snapped and was going wild in the air. Half of the painting was in darkness because of those who didn’t believe in Christ. Jesus was at the back of the ship very calmly looking towards the light, suggesting that the turbulence might be about to end. What strikes me is how comfortable He was in the midst of all that danger. Everyone is working to save his neck and He’s the only one that isn’t working at all. That’s how you know He’s God ✦ I don’t remember Jesus at all in the painting, I don’t remember seeing Christ…It was Rembrandt’s only seascape, a very luscious painting that always enlivened me. It just felt like your adrenaline picked up when you looked at the picture. The tumultousness and the chaos were very contagious. I don’t remember this painting as color. Action, not color ✦ It’s a very green picture, but it’s also very gold. I can’t remember why in the middle of this big storm, it’s so gold. The painting is just sort of suffused with this golden light ✦ The light on the people was amazing. It lifted them out of the darkness of the storm. There was this blinding concentration of light towards the point of danger with yellows, greens and blues in the center of the agitation. The frame was gigantic, late 19th century oiled gilded frame, very thick, very carved ✦ The colors were actually quite bright on the ship, purples, reds, whites. They kind of stood out from the black background. The waves might have had white tips to induce the stormy feeling. i loved the delicacy of the foam which was whitish and yellow and how he approached that with small strokes ✦ When I was a youngster, one Christmas, a dear family friend gave me a five-pound box of candy in a tin box. And on the lid was The Storm in the Sea of Galilée. It was the first time I’d ever seen it. It was my prized possession. I loved it, absolutely loved it.

Edition 1 of 2

(Inventory #30284)

Born

Paris, France, 1953

French conceptual artist Sophie Calle has redefined through personal investigation the terms and parameters of subject/object, the public versus the private, and role-playing. In her conceptual projects, Calle immerses herself in examinations of voyeurism, intimacy and identity. Calle’s “method” of dealing with the suffering the world throws at her is to see it all as a game of chance and coincidence, a ritual ripe for exposure on a wall.

The daughter of a doctor who collected pop art and a press officer mother, Calle never went to art school. She keeps no sketchbooks. “Ideas just come to me,” she has said. After completing her schooling, Calle took off to travel the world for seven years. When she came back to Paris in 1979, she began following and photographing strangers as a way to become reacquainted with the city and its people. In the process of secretly investigating, reconstructing or documenting strangers’ lives, Calle manipulates situations and individuals, and often adopts guises. Calle is fascinated by the interface between our public lives and our private selves. This has led her to investigate patterns of behavior using techniques akin to those of a private investigator, a psychologist, or a forensic scientist. It has also led her to investigate her own behavior so that her life, as lived and as imagined, has informed many of her most interesting works. Calle’s projects, with their suggestions of intimacy, also questioned the role of the spectator; viewers often feel a sense of unease as they became the unwitting collaborators in these violations of privacy. Moreover, the deliberately constructed and thus in one sense artificial nature of the documentary ‘evidence’ used in Calle’s work questioned the nature of all truths.

Calle’s work has been shown at the 1990 Sydney Biennial and the 1993 Biennial Exhibition of the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, and has been included in exhibitions at the Musee d’art Moderne de la Ville de Paris; De Appel, Amsterdam; the Whitechapel Art Gallery, London; The Clocktower and The Museum of Modern Art, New York; Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Hayward Gallery, London; Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago; Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris; the Serpentine Gallery, London, and Tel Aviv Museum of Art, Israel. In

2007, Calle showed in French Pavillion at the Venice Biennale. Her exhibit, entitled “Take Care of Yourself”, named after the last line of the message her ex had left her, won her international critical acclaim.

Calle currently lives and works in Paris, France.

10 Newbury Street, Boston, Massachusetts 02116

617-262-4490 | info@krakowwitkingallery.com

The gallery is free and open to the public Tuesday – Saturday, 10am – 5:30pm