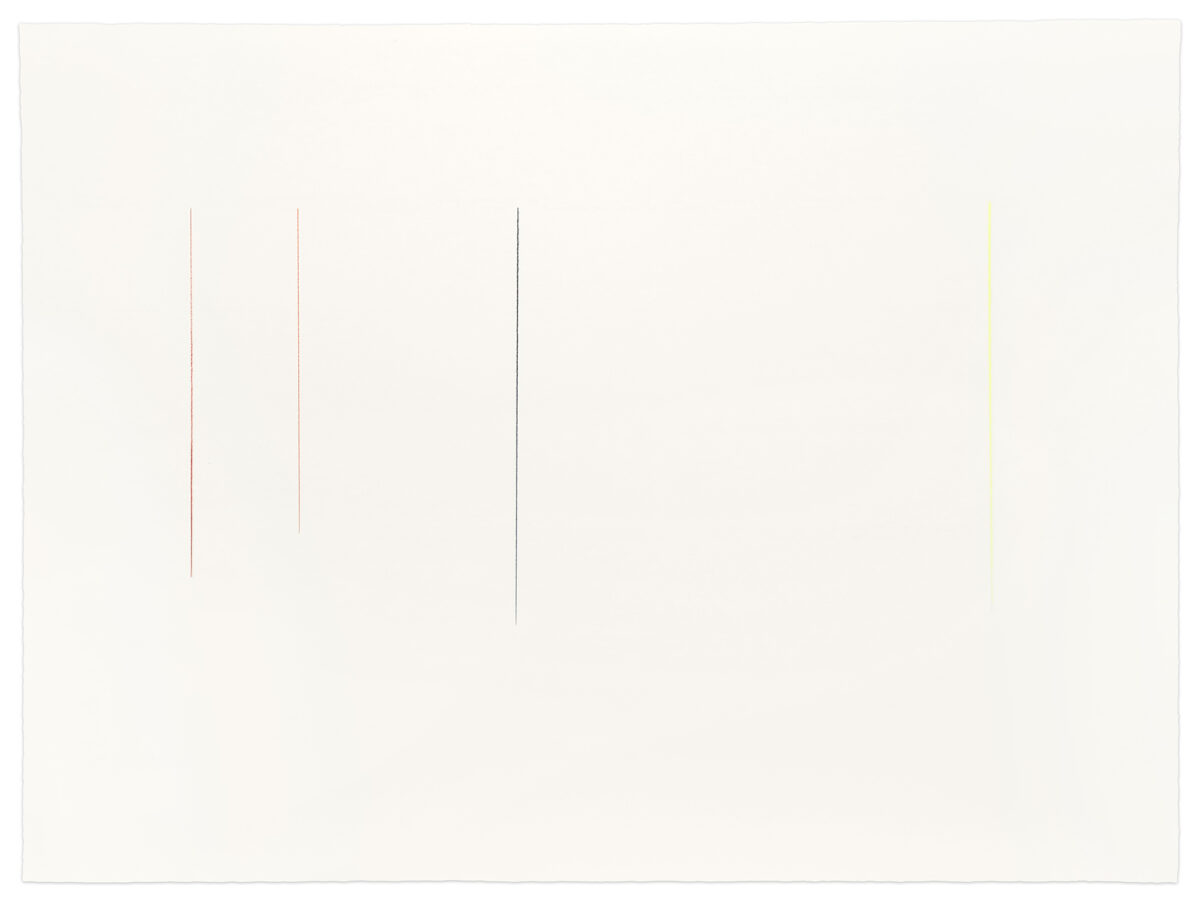

21 7/8 x 29 7/8 inches (55.6 x 75.9 cm)

Titled, signed, dated verso at bottom

(Inventory #36306)

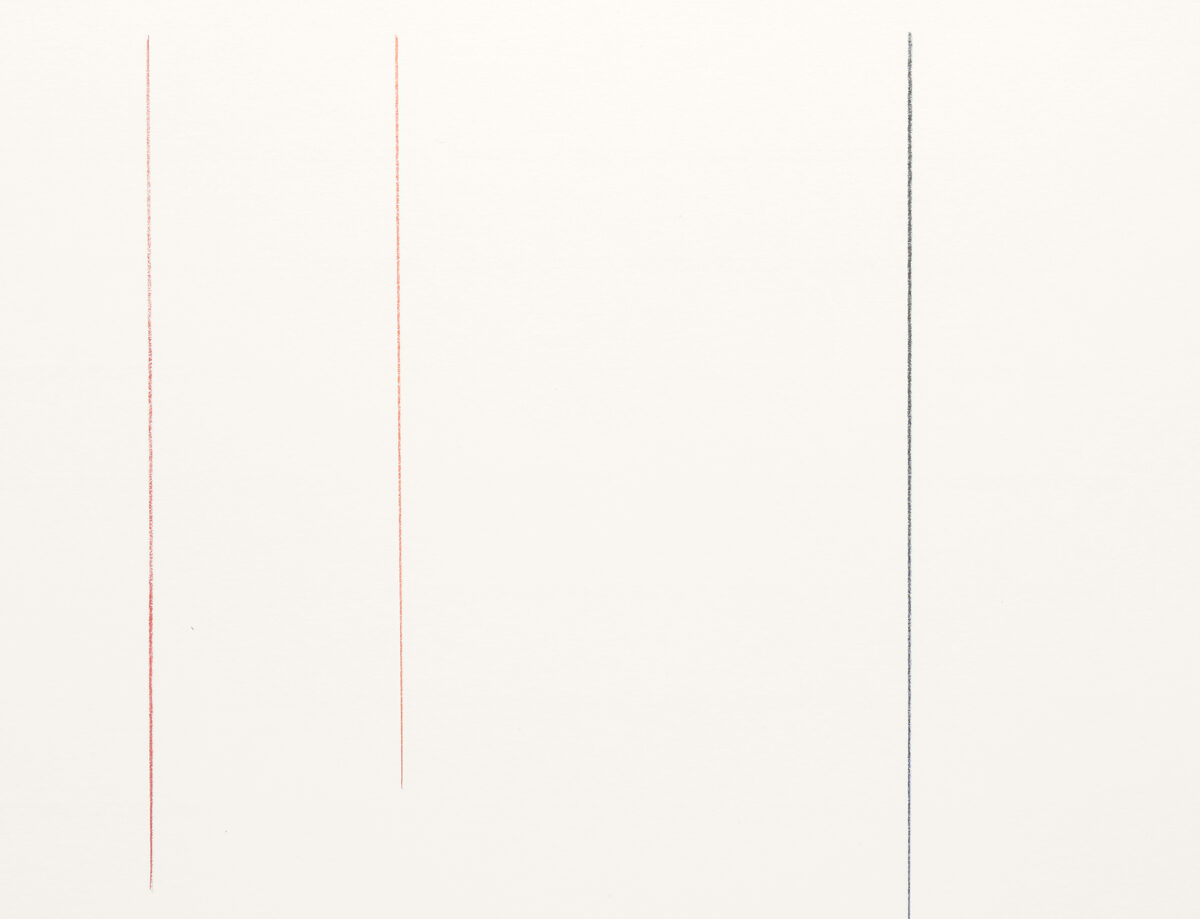

21 7/8 x 29 7/8 inches (55.6 x 75.9 cm)

Titled, signed, dated verso at bottom

(Inventory #36306)

In a 2009 review of the exhibition One More at Thomas Rehbein Gallery in Cologne, George Imdahl proclaimed that Janet Passehl’s ironed cloth work “turned the gallery into a church of high minimalism”. Since then her work has been included in several shows in Germany, including Art & Textile: Fabric as Material and Concept in Modern Art from Klimt to the Present, Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg and Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, 2013. Subsequent shows at Thomas Rehbein Gallery include a two-person show in 2019 featuring her pendant folded and cut fabric works. A review on Art Düsseldorf (web) pronounced her work “. . . minimal in its structure and arrangement, subsequently sublime in its aura and strivingly sensual in its layers.”

Passehl has exhibited at galleries in New York City including the Drawing Center, Zürcher Gallery, ODETTA, and 57W57Arts. Additionally, her work has been shown at the Wadsworth Atheneum, the Tang Museum, Mass MoCA, Tegnerforbundet in Oslo and Stalke Gallery in Copenhagen. She is represented in several museum and private collections.

Passehl is also a writer. In 2019, her visual art and poetry were featured together for the first time in States and Senses in Sydney, Australia. This was her fourth exhibition in that country. In 2021, her poetry was featured as an audio installation in The Feuilleton: I Will Bear Witness, in an abandoned news stand in Spoleto, Italy. Passehl is the author of the poetry collection Clutching Lambs (Negative Capability Press, 2014).

Artist Statement

Light, gravity, space. Time and duration. Attentiveness. These have been my concerns for decades, explored first through linear drawings, and then also through simple acts performed on plain cloth: folding, ironing, cutting, draping, hanging. I try to collaborate with the nature of the material, allow it to be itself.

Cloth has two wills: the will to flatness and the will to drape. Not antagonistic but coexistent.

In 2021 I learned how to weave plain cloth, and acquired an old loom. The weaving process embodies the qualities noted above, and the weavings tell the story of their making. The loom is a body. It is not threaded, like a needle. It is “dressed”. During the dressing process, every one of hundreds of warp threads are touched many times. Thread must be nurtured through the loom. The process takes hours and is mathematical and rational, and sometimes chaotic. Entanglements happen. Dressing the loom is a strange kind of intimacy.

It is through material, via the senses, that we may catch a glimpse of something beyond the known world. Material is not the veil, but the translator, the guide, the conduit. It is for this glimpse that I persistently spend time in the studio, touching cloth and paper, moving threads around, watching light reflected, refracted, and absorbed, the making and unmaking of shadows. Allowing gravity its pull. I weave the cloth, but the work is complete only when it is hung. It is completed by its own weight and the phenomena around it.

Same thread, same weave, similar dimensions, over and over. The rigor and insistence of Agnes Martin and Daniel Buren are on my mind. Buren also because of his engagement with space and architecture. Martin because she is also a romantic. Each of them because of their radically pared down vocabularies. At the same time, I think of Bonnard, who makes emptiness traverse a painted room so that the canvas becomes a spatial and temporal field. Who is a master of differentiating interior and exterior light. There is Zurbaran’s pristine white cloth, with the fold. And Renaissance annunciation paintings—the upright angel, the virgin drooping beneath the weight of her assignment, the heavy drapery, pulling itself groundward.

There was my early childhood experience of the overwrought aesthetics of the 1960s Catholic church, and what I took away from it: the plain white altar cloth.There are Donald Judd plywood boxes, almost confrontational in their plainness (What is this? Deal with it.). More an encounter than a visual experience. And his subtle, almost kinetic, variations of proportion, angle, and cadence. Also his deliberately tempered level of craft. There is Canaletto’s architectural geometry and the intimacy of daily life playing out within it. There was the back of a Howardena Pindell canvas I had the privilege of seeing when I worked at a museum thirty-five years ago—monochrome off-white, hand-cut and then hand-sutured back together. As much story told there as in the painted imagery on the front. A seminal moment was when Kazuko Miyamoto showed me how to fold a kimono—the ritualistic precision of folding, the formal ideal of the rectangle in gentle opposition to the mutable nature of cloth.

It is within that moment of slippage that my practice is grounded—on the elusive bridge between stasis and movement, intellect and emotion, control and leniency, tension and grace.

Janet Passehl 2023

10 Newbury Street, Boston, Massachusetts 02116

617-262-4490 | info@krakowwitkingallery.com

The gallery is free and open to the public Tuesday – Saturday, 10am – 5:30pm