Edition of 60, P.S. (Special Proof)

Frame size: 40 1/4 x 60 1/4 inches (102.2 x 153 cm)

Signed on sheet stamped IX and numbered “P.S.” on colophon

(Inventory #31648)

Edition of 60, P.S. (Special Proof)

Frame size: 40 1/4 x 60 1/4 inches (102.2 x 153 cm)

Signed on sheet stamped IX and numbered “P.S.” on colophon

(Inventory #31648)

“The attention is analytical, but the result is enigmatic.” (Giulio Paolini)

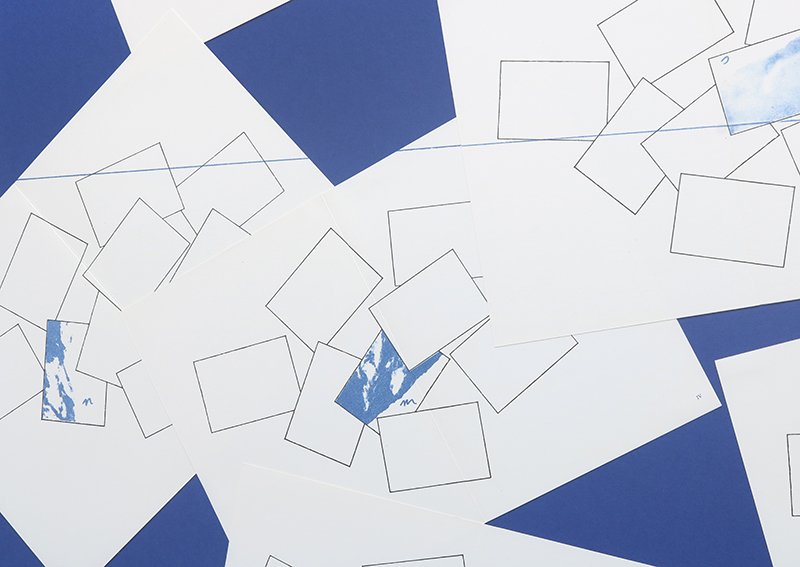

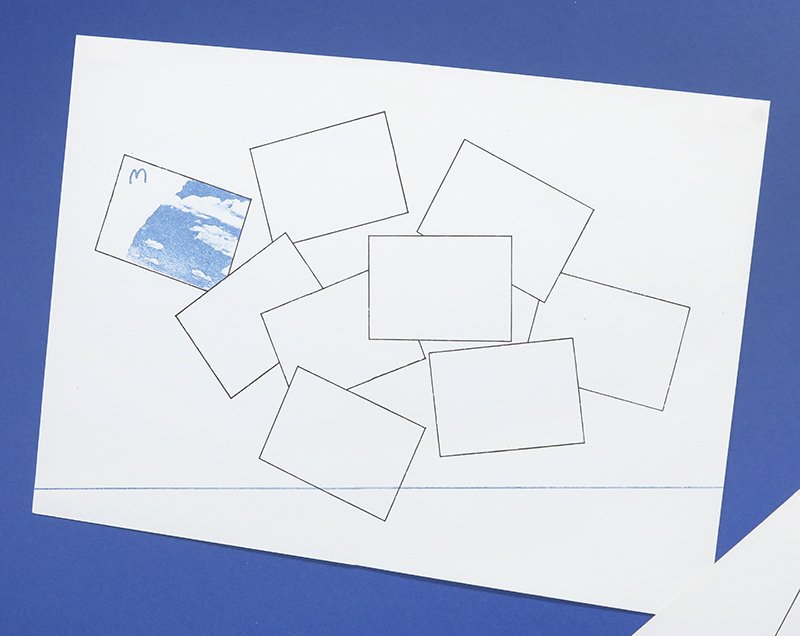

Giulio Paolini has explored issues of control and comprehension using collage, perspective and quotation for much of his life. In “Nove particolari in due tempi (Nine Details in Two Stages),” Paolini’s appropriated image of the figure is not in the center, but off to the right. The perspectival lines are not connected to the right (writing/drawing) hand of the figure, but closer to the left eye and/or the raised left hand. In the overall composition, Paolini balances between centrifugal and centripetal forces where the left goes right, the right goes left and hierarchy (between artist, viewer, subject matter, source material and end result) is always in question. Looking further at the figure, its image can be read as being taken from “the past” on account of its enlarged engraving-like lines (the image is taken from a seventeenth-century handbook about perspective, “Les Perspecteurs” by Abraham Bosse). The reproduced lines are contrasted by the rigidly clean and geometric rectangles on the other sheets of paper as well as by the straight but hand-drawn lines that unify the overall composition. In addition, the images of what can be read as clouds or the sea are also, visibly, reproductions (on account of their image-grain) and so, not only are they hazy on account of the imagery, but also on account of the images being multiple steps away from their source. Paolini’s use of reference expands the meaning of the work and also serves to acknowledge and focus on the idea of “reference” as a forever-morphing aspect of life. Order (perspective, predetermined diagrams on each sheet showing the placement of each piece of paper in the overall composition, every sheet representing the scheme of the whole work) and chaos (the seemingly haphazard, strewn-about quality of the sheets of paper), the past and the present, the actual and the reproduced – these are all subjects within “Nove particolari in due tempi (Nine Details in Two Stages)” and subjects with which Giulio Paolini has spent over fifty years exploring through works on paper, installations and writing.

Giulio Paolini has had numerous exhibitions in art galleries and museums around the world. Among the largest are those that have been held at Palazzo della Pilotta in Parma (1976); Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam (1980); Nouveau Musée in Villeurbanne (1984); Staatsgalerie in Stuttgart (1986); Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna in Rome (1988); Neue Galerie am Landesmuseum Joanneum, Graz (1998); GAM Galleria Civica d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, Turin (1999); Fondazione Prada in Milan (2003); Kunstmuseum in Winterthur (2005); MACRO Museo d’Arte Contemporanea Roma (2013); Whitechapel Gallery, London (2014); and Castello di Rivoli -Museo d’Arte contemporanea (2020), Turin. Paolini has participated four times in Documenta in Kassel (1972, 1977, 1982, 1992) and ten times at the Venice Biennale (1970, 1976, 1978, 1980, 1984, 1986, 1993, 1995, 1997, 2013).

Giulio Paolini was born on November 5, 1940 in Genoa. Throughout his career, Giulio Paolini has been fixated on the act of seeing as well as the relationship between the seer and the seen. Emerging in the context of the Italian Arte Povera artists of the 1960s, he shared with his cohorts a profound mistrust of the commodity status assigned to traditional media such as painting. Working in a historical moment that saw the ascendancy of painting in the 1960s in the form of American Abstract Expressionism and the European Art Informel, Paolini took an iconoclastic position, suggesting that the medium was a “question without an answer.” He chose instead to embark on a conceptual exploration of the parameters of painting’s status within our culture as well as its physical structure, or what he has called “the space of painting.” 1 His Delfo (Delphi) (1965) is a perfect example of the artist’s early structural investigations into the nature of painting and its relationship to seeing. Taking its title from the oracle of Delphi, a “seer’ in Greek antiquity who dispensed prophecies, the image is a photographic self-portrait of the artist wearing dark glasses and confronting the viewer from behind the wooden support bars of an unstretched painting. After he transferred this image to a piece of canvas through a photographic process, Delfo became a hybrid object that is both a photograph and a painting, yet at the same time is neither. It is paradoxically a work that refuses both the status and the act of painting while self-reflexively emphasizing the philosophical implications of the hidden physical support structure of that medium. In a very real sense then, Paolini has made painting the content of this work without ever putting brush to canvas.

If Delfo asks us to consider the implications of what lies physically beneath a painting’s surface, it also brings into play a discussion of seeing and being seen. Is the artist himself the seer suggested by its title? Though he looks out at the viewer from behind the surface of a painting, neither artist nor spectator can fully meet the other’s gaze, as their views are blocked by the conceit of the reproduced stretcher bars. This frustrating short-circuiting of the relational act of seeing and being seen raises issues regarding vision as well as painting. The question that is begged is how do we see the work of art, but more importantly, how does that work of art see us? This play of vision foreshadows future works by Paolini such as Mimesi (Mimesis) (1976-1988), a sculpture consisting of a pair of identical plaster copies of Praxiteles Hermes that are turned to face each other, their eyes caught in a Narcissistic feedback loop of seeing and being seen. Both works invoke the legacy of art history’s fascination with vision and looking that stretches back at least to Diego Velasquez’s Las Meninas (1656), a painting that is as much about the possibilities of making a picture as it is about the relationship between the seer and the seen. In light of this, Paolini’s work looks toward the conceptual future of art-making as much as it does to its past.

Quotes in this paragraph are from Paolini, conversation with Francesco Bonami, Richard Flood, and Kathy Halbreich in the artist’s studio in Turin, Italy, September 27, 1997 (transcript, Walker Art Center Archives).

Fogle, Douglas. Giulio Paolini. In Bits & Pieces Put Together to Present a Semblance of a Whole: Walker Art Center Collections, edited by Joan Rothfuss and Elizabeth Carpenter. Minneapolis, MN: Walker Art Center, 2005.

© 2005 Walker Art Center

10 Newbury Street, Boston, Massachusetts 02116

617-262-4490 | info@krakowwitkingallery.com

The gallery is free and open to the public Tuesday – Saturday, 10am – 5:30pm