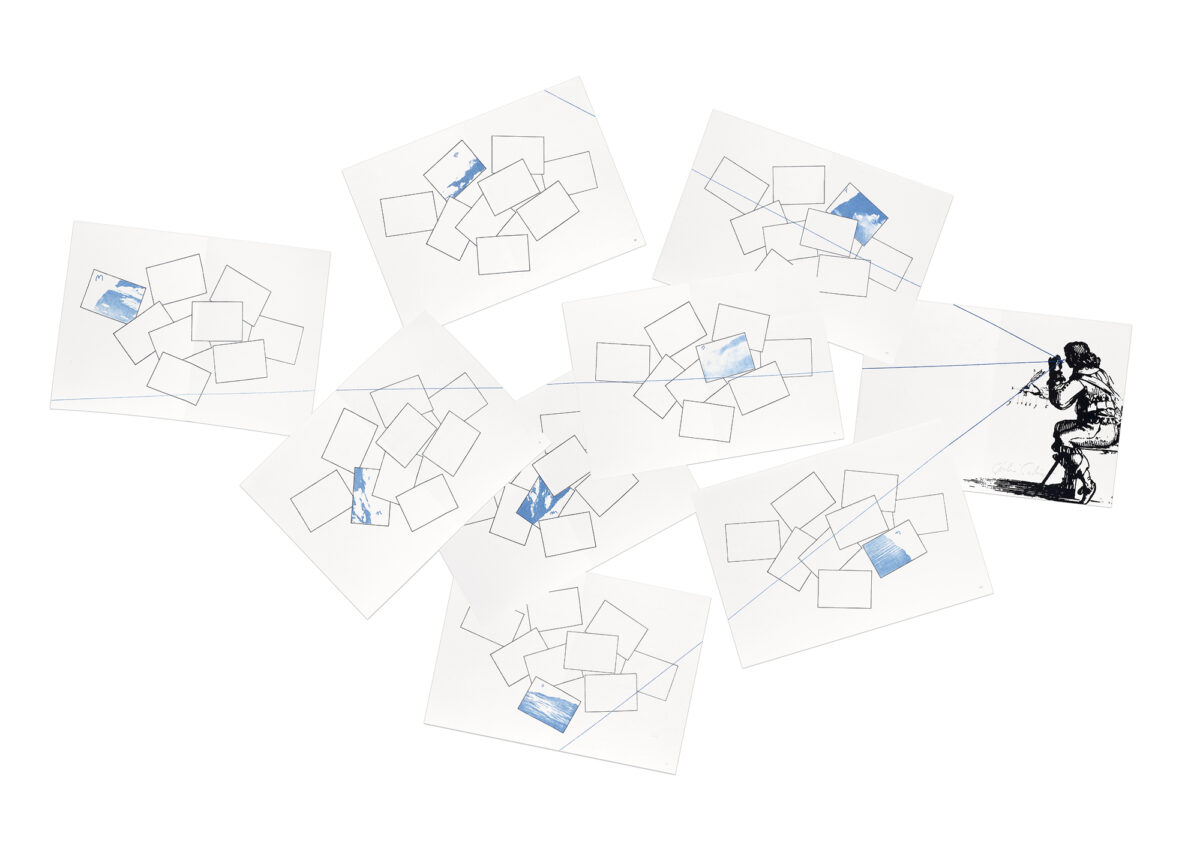

Overall arrangement size: 39 5/16 x 59 inches (100 x 150 cm)

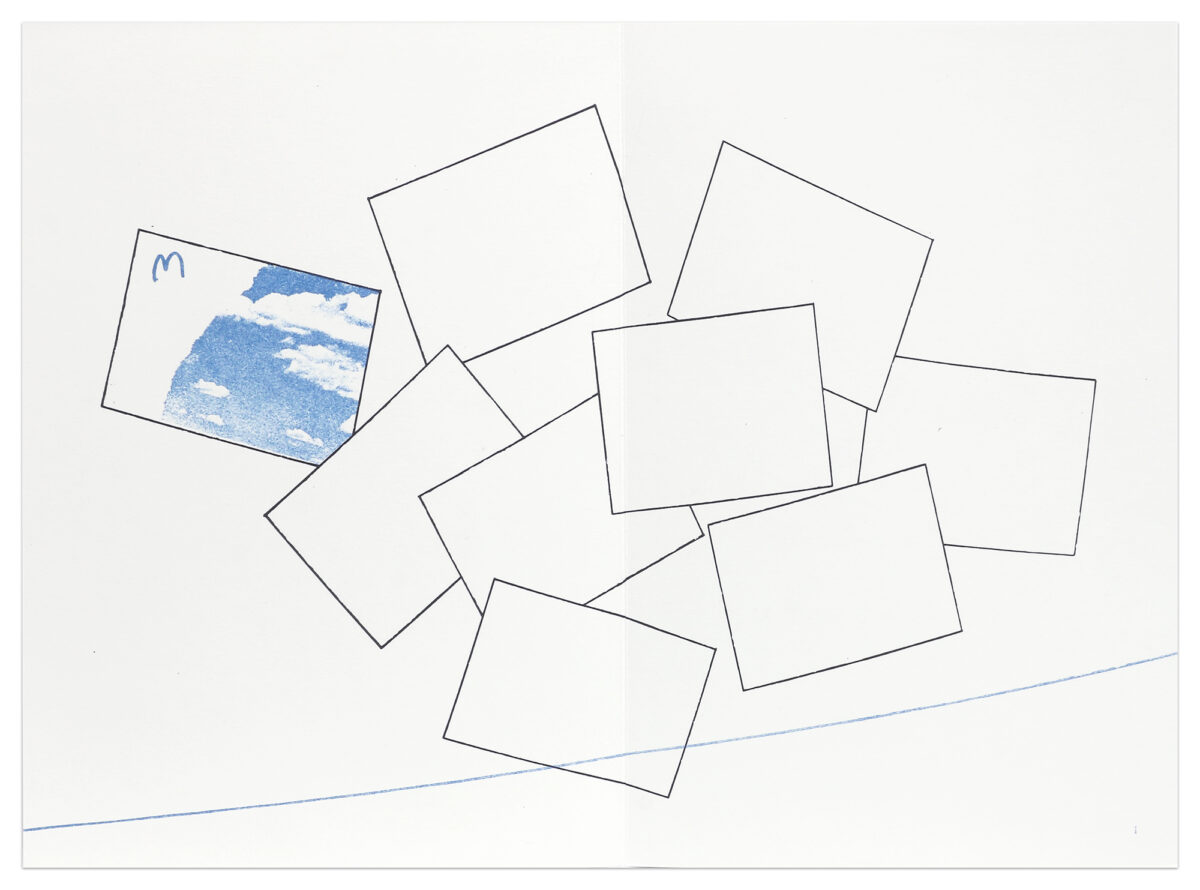

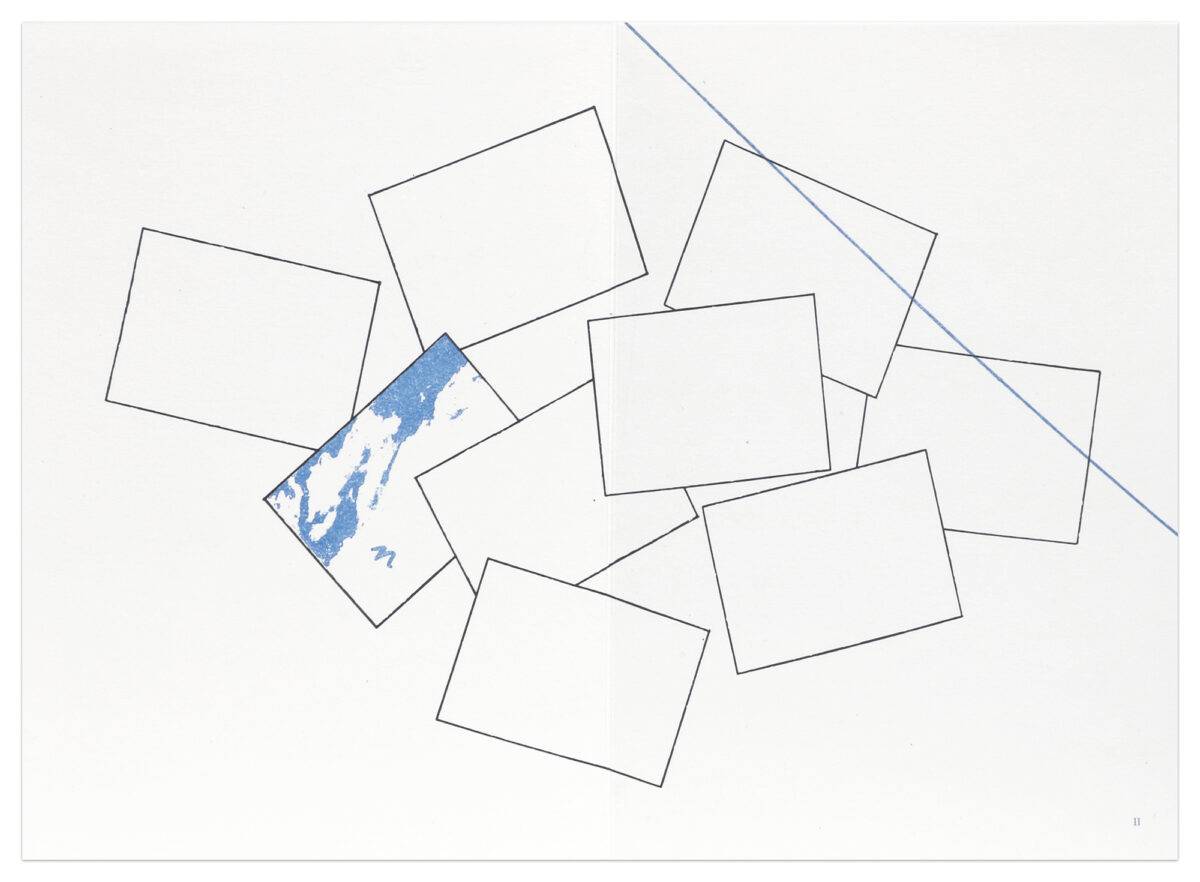

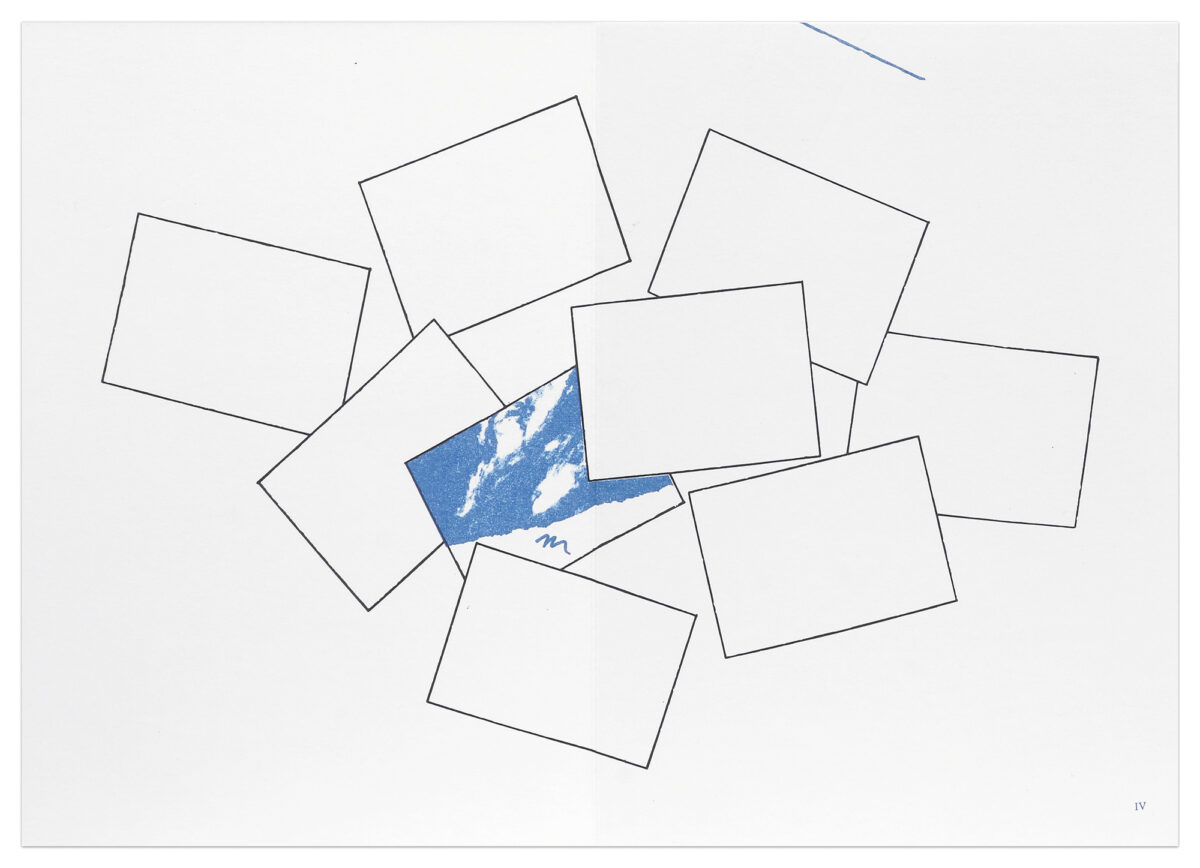

Paper size (each): 6 9/16 x 9 1/2 inches (17 x 24 cm)

Edition of 60

Signed and numbered recto in graphite

(Inventory #35483)

Overall arrangement size: 39 5/16 x 59 inches (100 x 150 cm)

Paper size (each): 6 9/16 x 9 1/2 inches (17 x 24 cm)

Edition of 60

Signed and numbered recto in graphite

(Inventory #35483)

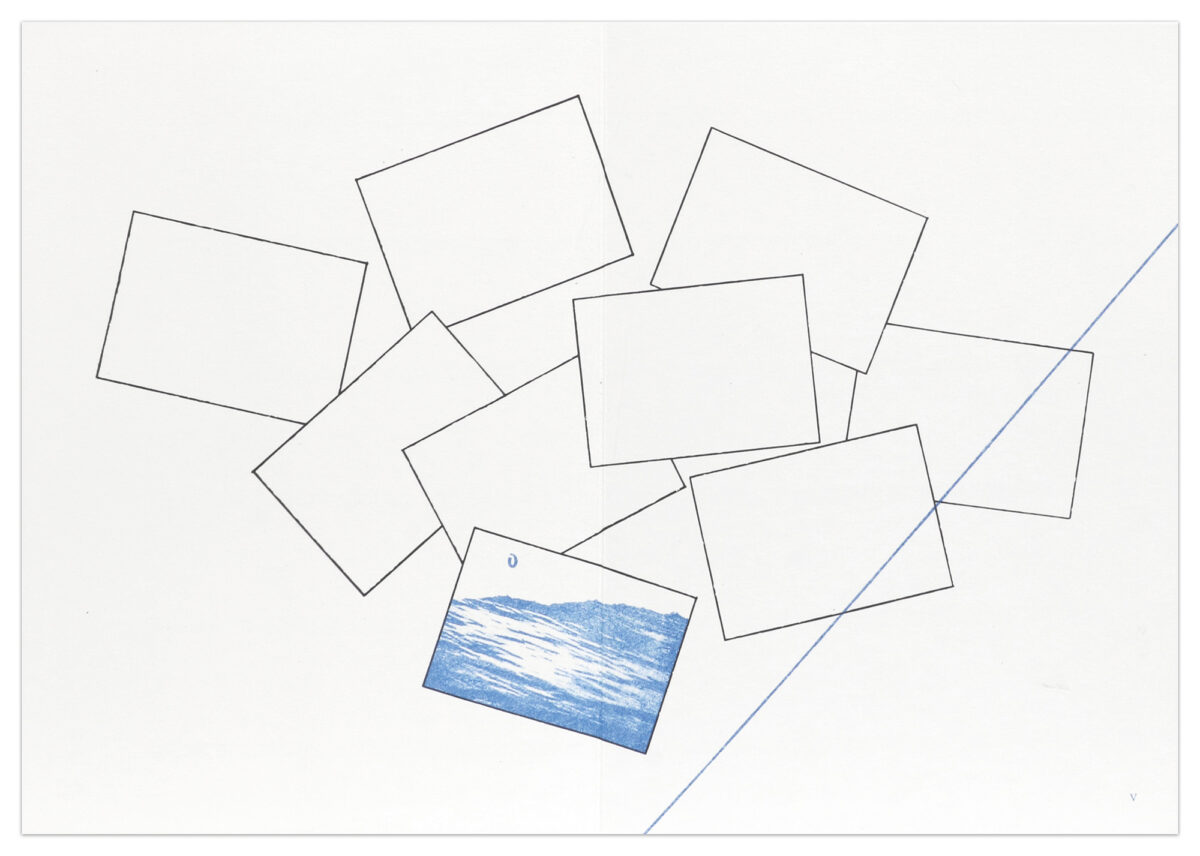

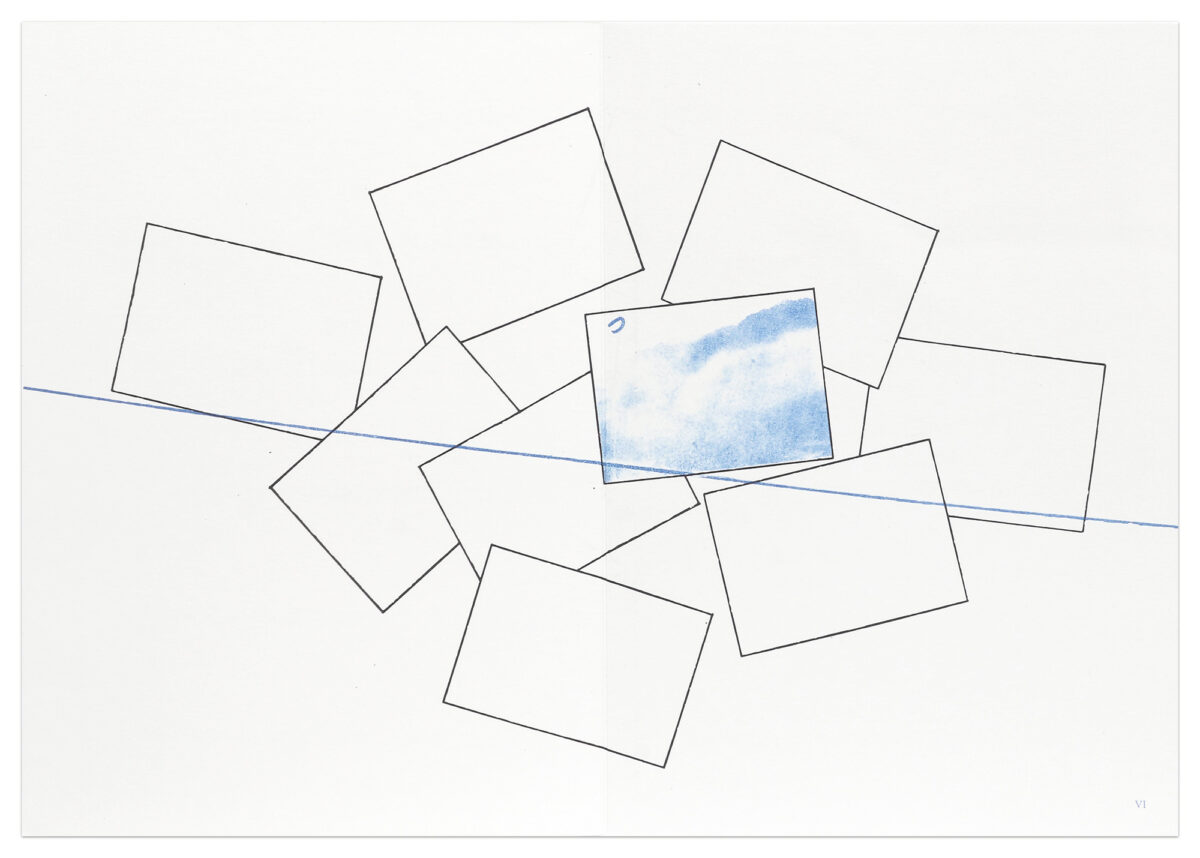

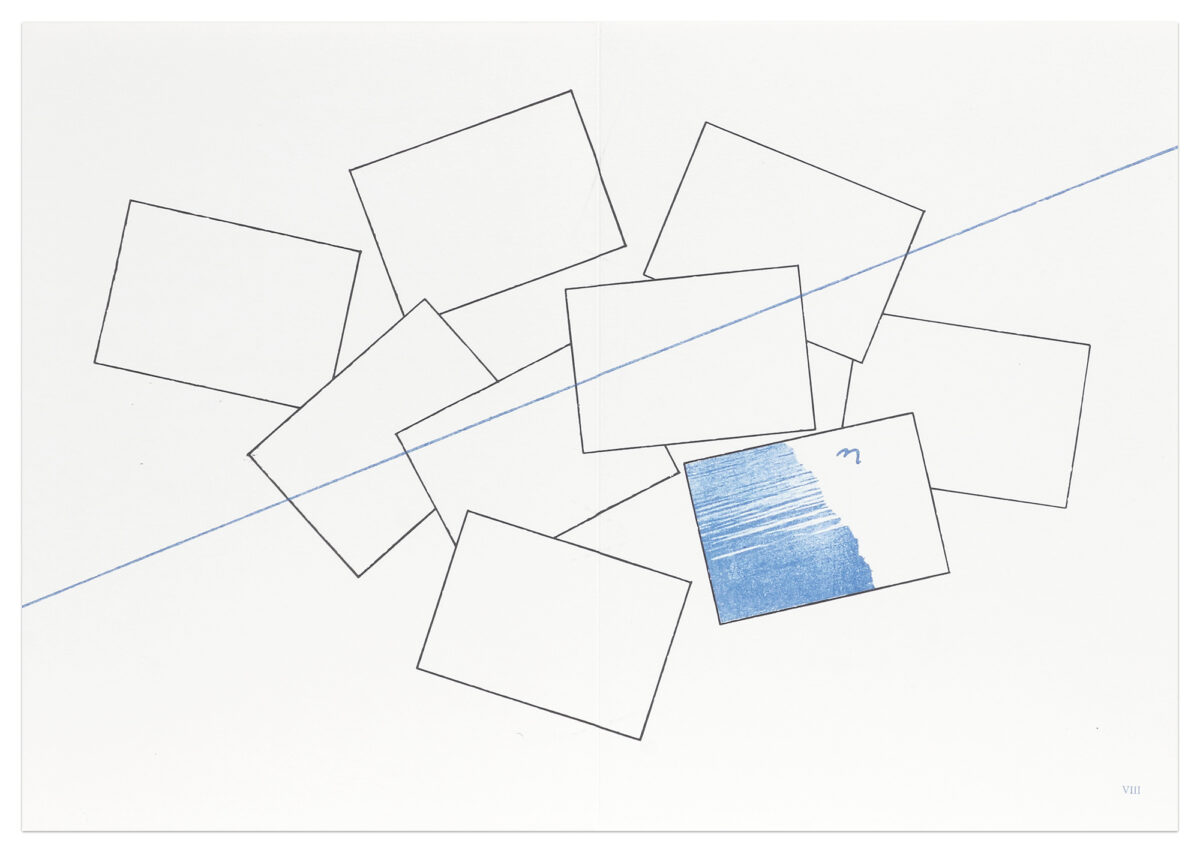

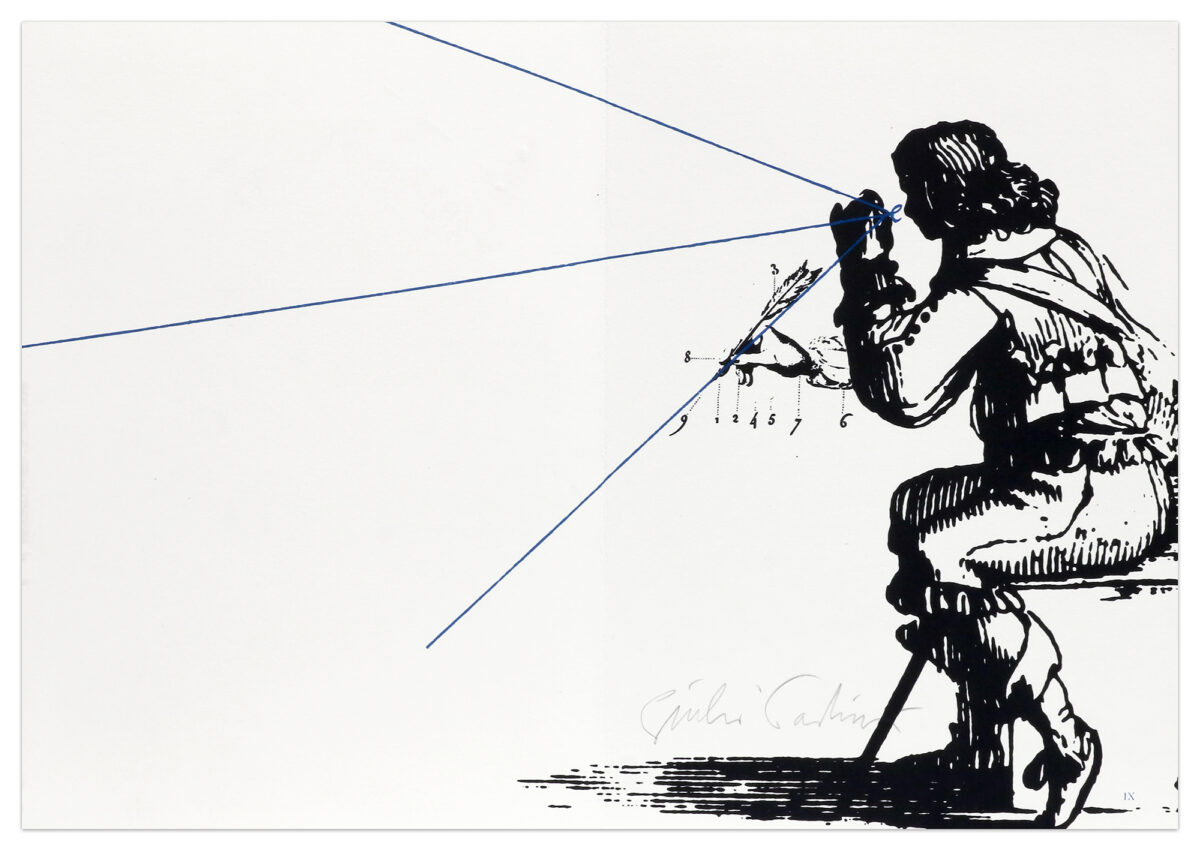

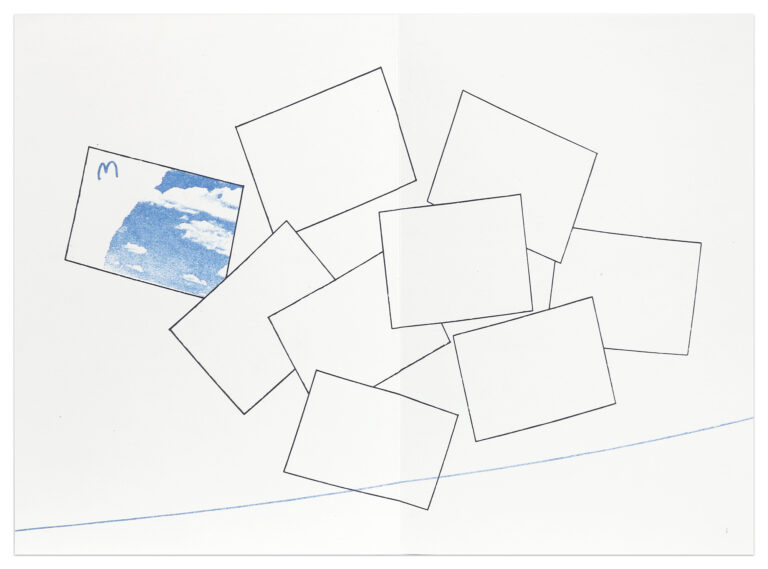

The ensemble of nine sheets originates from the plate that reproduces a male figure (taken from Abraham Bosse’s handbook on perspective, Les perspecteurs, 1647-48), associated with the reproduction of a hand intent on drawing (borrowed from Diderot’s Encyclopédie). When the work is displayed – following the artist’s instructions – the drawing of the visual cone extends to the other eight sheets, each of which reproducing the ensemble of the nine plates. In each sheet, the rectangle corresponding to the position of the sheet itself in the entire composition is marked by a fragment that reproduces a view of the sea (in the sheets below the median “horizon line”) or of the sky (in the sheets above the median axis). Each of the blue rectangles also features the inscription of a letter, so that together they spell out the name Mnemosyne, the mother of the nine Muses. The title refers to the nine sheets included in the edition and the possibility of using the object at two different stages: as a closed volume or as an open composition, to be arranged on the wall. Nove particolari in due tempi aims to be a tribute by the artist to the device of vision, in a synthesis between historical sources and his very own language.

Giulio Paolini was born on November 5, 1940 in Genoa. Throughout his career, Giulio Paolini has been fixated on the act of seeing as well as the relationship between the seer and the seen. Emerging in the context of the Italian Arte Povera artists of the 1960s, he shared with his cohorts a profound mistrust of the commodity status assigned to traditional media such as painting. Working in a historical moment that saw the ascendancy of painting in the 1960s in the form of American Abstract Expressionism and the European Art Informel, Paolini took an iconoclastic position, suggesting that the medium was a “question without an answer.” He chose instead to embark on a conceptual exploration of the parameters of painting’s status within our culture as well as its physical structure, or what he has called “the space of painting.” 1 His Delfo (Delphi) (1965) is a perfect example of the artist’s early structural investigations into the nature of painting and its relationship to seeing. Taking its title from the oracle of Delphi, a “seer’ in Greek antiquity who dispensed prophecies, the image is a photographic self-portrait of the artist wearing dark glasses and confronting the viewer from behind the wooden support bars of an unstretched painting. After he transferred this image to a piece of canvas through a photographic process, Delfo became a hybrid object that is both a photograph and a painting, yet at the same time is neither. It is paradoxically a work that refuses both the status and the act of painting while self-reflexively emphasizing the philosophical implications of the hidden physical support structure of that medium. In a very real sense then, Paolini has made painting the content of this work without ever putting brush to canvas.

If Delfo asks us to consider the implications of what lies physically beneath a painting’s surface, it also brings into play a discussion of seeing and being seen. Is the artist himself the seer suggested by its title? Though he looks out at the viewer from behind the surface of a painting, neither artist nor spectator can fully meet the other’s gaze, as their views are blocked by the conceit of the reproduced stretcher bars. This frustrating short-circuiting of the relational act of seeing and being seen raises issues regarding vision as well as painting. The question that is begged is how do we see the work of art, but more importantly, how does that work of art see us? This play of vision foreshadows future works by Paolini such as Mimesi (Mimesis) (1976-1988), a sculpture consisting of a pair of identical plaster copies of Praxiteles Hermes that are turned to face each other, their eyes caught in a Narcissistic feedback loop of seeing and being seen. Both works invoke the legacy of art history’s fascination with vision and looking that stretches back at least to Diego Velasquez’s Las Meninas (1656), a painting that is as much about the possibilities of making a picture as it is about the relationship between the seer and the seen. In light of this, Paolini’s work looks toward the conceptual future of art-making as much as it does to its past.

Quotes in this paragraph are from Paolini, conversation with Francesco Bonami, Richard Flood, and Kathy Halbreich in the artist’s studio in Turin, Italy, September 27, 1997 (transcript, Walker Art Center Archives).

Fogle, Douglas. Giulio Paolini. In Bits & Pieces Put Together to Present a Semblance of a Whole: Walker Art Center Collections, edited by Joan Rothfuss and Elizabeth Carpenter. Minneapolis, MN: Walker Art Center, 2005.

© 2005 Walker Art Center

10 Newbury Street, Boston, Massachusetts 02116

617-262-4490 | info@krakowwitkingallery.com

The gallery is free and open to the public Tuesday – Saturday, 10am – 5:30pm