Installation measurements vary

(Inventory #22635)

Installation measurements vary

(Inventory #22635)

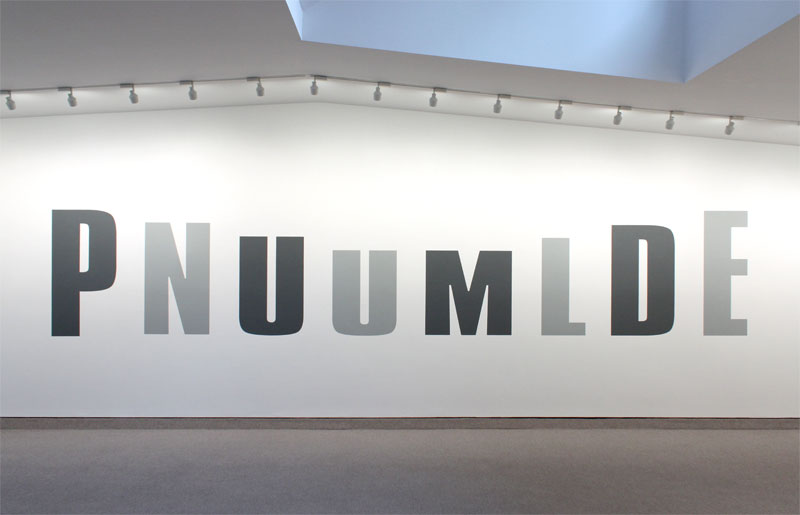

In order to model itself after its real life counterpart, PENDULUM’s letters have to be completely reordered. The new order, PNUUMLDE, reflects the successive stations of a pendulum’s arc as it swings back and forth across an imaginary center between the first and last letters, the second and seventh, the third and sixth, and the fourth and fifth, punctuating each one with a change of direction. The sequence of letters is deliberately out of order linguistically but in order conceptually. While the word does not actively move, it serves as a kind of score for reading which the viewer activates each time they read it. As they attempt to spell it correctly by visually reordering the letters, their repeated eye movements back and forth between P and E, N and D, U and L, and U and M mimic the pendulum’s motion. It is an unintelligible jumble of letters until the viewers set it in motion. The reader generates the pendulum, whose alternating rhythm is reinforced by its black and white palette.

Color, sequence, and incidence of letters are important to the way words play out their message, but in issues of polarity numbers are important too, as in any situation involving two sides. PENDULUM is stabilized by balance. Its even-numbered letters, four on each side of the center, methodically record each stroke to the right and left by the virtual pendulum. When it swings one way, it can be assured by gravity and momentum that it will swing back by that much the other way. The center here is not the subject of colonization, but the fixed point against which the equal distance to each side is measured. Within a word, that distance is measured by the number of letters. If pendulum did not have even-numbered letters, it would not have worked.

— from The Center Is a Concept, Kay Rosen.