The Abstracted Image in Photography, on view at the Barbara Krakow Gallery from 9 December through 24 January is a group photography show which examines abstracted landscape photography, including works by Carl Chiarenza, Thomas Joshua ooper, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Jan Henle, Gerhard Richter, Hiroshi Sugimoto, James Welling and Lisa Young.The exhibition’s theme rests n artists who have photographed with a non-narrative intent, natural, as well as constructed landscapes. In these works, the landscape has become an abstracted view of reality. No interpretations aregiven byond what the artist has allowed. Viewer’s are supplied with little more than a whisper of information about the location, subject or artist’s purpose, and are instead left to develop their own interpretations. In this vein, the work exhibited focuses aestheticaly on texture, shape and gradations of hue.

Hiroshi Sugimoto, nationally and internationally recognized for his unmistakable, minimal, black and white photographs of the sea, depicts image after image with the same format–sky above and sea below–varying only the light and tme of day. At first glance, each photograph appears the same; however, what gradually and deliberately beomes revealed through the seemingly repetitious visions are the subtle differences within each, which in turn reveal Sugimoto’s whole artistic vision. Sugimoto’s work does not strive to define and explain the world, but rather, to reveal it gradually through unwavering perception and observation.

Thomas Joshua Cooper’s seascapes differ from Sugimoto’s in the emotional intensity of the image. While Sugimoto keeps his photographs still and silent–devoid of any human presence, Cooper considers himself to be a story teller, his art to be a narration, and describes his photographs as “filled with gesture and luminous tone.”

Gazing is my primary physical activity. Stillness and silence surround and submerge event. Nothing happens, nothing ever seems to happen. Anticipation builds and extends. Waiting is no longer recognizable or quantifiable. The picture space is opening up and out. In the precarious emptiness and density of these luminous visual spaces we are simply left alone, alone with ourselves.

Cooper photographs places which he considers often traversed, and always overlooked, striving to create the extraordinary from the ordinary.

Gerhard Richter fills his photographs with an ardent emotion akin to Cooper’s, also endowing them with a dream-like quality. Based on his photographs of the Canary Islands, this portfolio of photogravure’s exemplifies Richter’s interest in depicting the simple, while using a blur to create an abstract quality that disguises its reality. “I cannot describe anything more clearly about reality than my own relation to reality. And this has always something to do with haziness, insecurity, inconsistency, fragmentary performance…” (Richter, exhibition catalogue for 36th Venice biennale, P. 24)

Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ continued interest in both revealing and eliciting emotions–especially feelings of loss– to and from the masses by using propaganda-as-art is epitomized by this project of billboard scale images depicting footprints in the sand. The larger-than-life undulations in the sand are a ghostly reminder of how fleeting life really is.

Like Gonzalez-Torres, Jan Henle uses sand as the subject for his “Topographical Film Drawings.” However, unlike Gonzalez-Torres, who leaves the footprints anonymous, Henle has specifically chosen the stretches of beach–beach where he played when he was a child. The photograph he has taken becomes the method for transferring his vision into a form that preserves the original feeling and impact.

I wanted something that, when it was up on the wall, would be not so much an object as an opening–so the viewer could have their own personal experience.

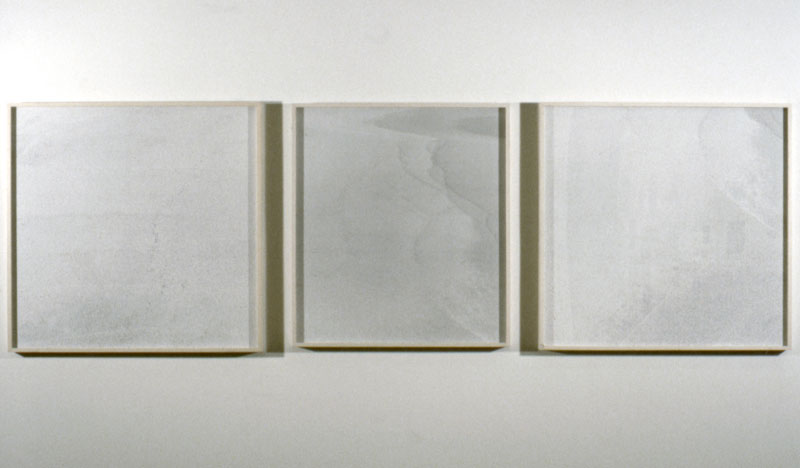

Boston artist Lisa Young combines acrylic and tinfoil over silver photographic prints to meld the real world with an artificial one, creating what she refers to as a “romantic vision of the natural wolrd.” The sublime yet rough-edged hand working lands the viewer in a dream state–somewhere betwixt and between the reality of the photograph and the surreality of the world Young has imposed on us.

Both James Welling and Carl Chiarenza fabricate their landscapes, using tinfoil, which as been crumpled, cut, collaged or otherwise manipulated to form abstracted shapes. Welling uses a small pictorial format, creating tiny universes within the crushed curves and folds of the foil. Using photography as the means to both create and justify the existence of an artificial world, the foil becomes a landscape because our imagination sees it as such. As Welling says, “I’m trying to locate a place outside of the dominating power of language where these sensual landscapes can exist.”

Chiarenza actually builds small constructions from tinfoil, scraps of paper, fabric and metal. he then photographs these diminutive collages–which are usually no more that 20″ in size–using a large format camera, and prints them in large sizes, creating grand scale images which hearken back to landscape photographs by Edward Weston and Ansel Adams. And, while the observer makes this connection, and sees the landscape within the tears and folds, Chiarenza reminds us that “…making art with photoggraphy is to pursue photography’s own special characteristics as a medium of transformation. Instead of trying to hide those characteristics in as illusion, I try to expose them, exploit them, underline the fact that the viewer is viewing a picture, not other things in the world.”

125 x 272 inches (317.5 x 690.9 cm)

Edition of 84

(Inventory #8799)

125 x 272 inches (317.5 x 690.9 cm)

Edition of 84

(Inventory #8799)

39 x 114 inches (99.1 x 289.6 cm)

(Inventory #8479)

39 x 114 inches (99.1 x 289.6 cm)

(Inventory #8479)

No results found.

10 Newbury Street, Boston, Massachusetts 02116

617-262-4490 | info@krakowwitkingallery.com

The gallery is free and open to the public Tuesday – Saturday, 10am – 5:30pm