In Pursuit of Lost Time–titled after the recent translation of Marcel Proust’s expansive novel — traces the history and explores the current manifestations of contemporary artists’ concerns with time, memory, and the re-presentation of performance-related activities. The exhibition features the work of sixteen established and emerging contemporary artists from all over the world.Neither documentation nor process, as such, is of concern for these artists; the experience of the objects they produce, like the taste of a madeleine for Proust’s narrator, not only enables a view onto a previous event or activity, but also contains and defines that event or activity — and that experience of the object is more than simply a metaphor for the event to which it refers: it becomes that event.

The artists grouped here owe a collective debt to the late Robert Smithson, recognized as a grandparent of landscape-based conceptual work in such grand-scale earthworks as Spiral Jetty, but who also engendered a generation of thought and work that takes its place simultaneously in- and out-side gallery spaces. His Site/Non-site works of the mid sixties placed natural mterials (in most cases, rock), derived from specific geographic sites, into generic gallery spaces alongside simple maps and other textual markers of those sites, thus raising questions of site-specificity, the power of referents to site, and, ultimately, the nature of ‘representation’ of objects and activities occurring outside not only the gallery space, but also the space of the objects representing them. The artists of In Pursuit of Lost Time raise similar questions of site and representation, extending Smithson’s formal innovations to include their diverse spiritual, political, social, and lyrical concerns.

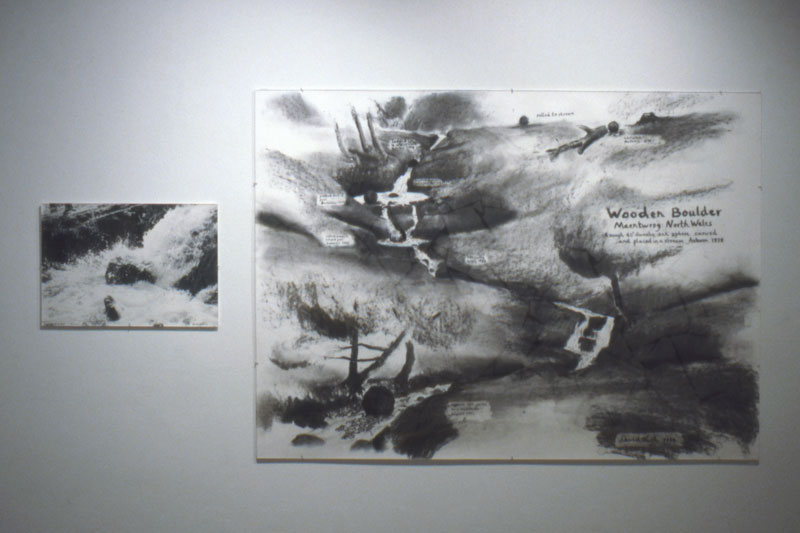

Several artists, for example, follow Smithson into landscape-based investigations: well-known British artists Hamish Fulton and Richard Long bring these themes to bear in various media–Long with his photo-and-text based descriptions of extended walks in specific sites, and Fulton with his painted and drawn descriptions of the intensely subjective sensations his journeys offer. Any Goldsworthy and David Nash–also British–also explore the landscape, using natural materials to create sculptural objects in specific sites; their photography and drawing, again, is the only trace of their elaborate activity. Boston-based Daniel Ranalli’s work finds its source at the water’s edge, where, also through photography, he realizes the effect of the tides over time or charts the instinctual moves of such small land-and-sea dwellers as periwinkles. Ana Mendieta, on the other hand, puts her own body in the scene: her photographs record the production of her ‘earth/body’ works, in which that body becomes a metaphorical link between earthly and spiritual practice.

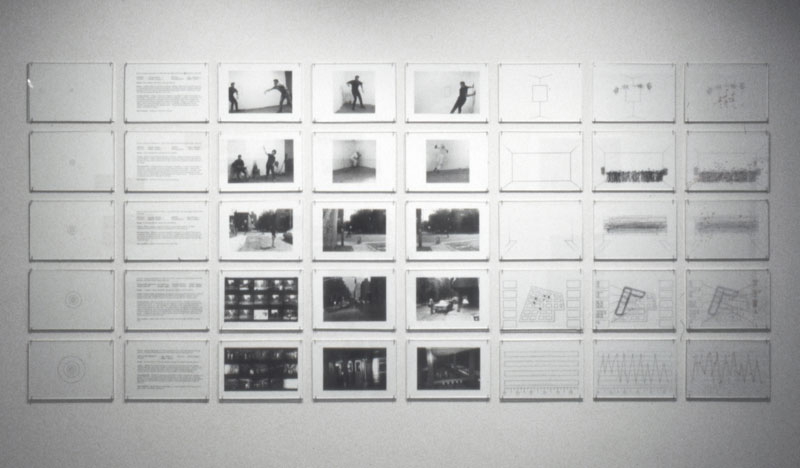

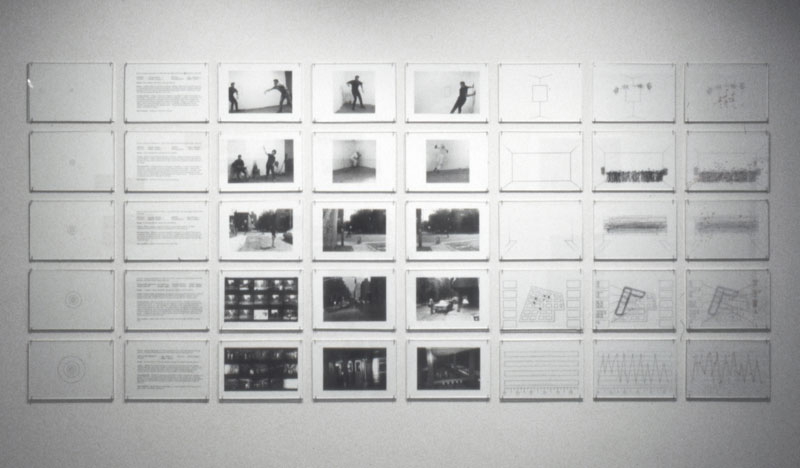

Such contemplative suggestions find a stranger, more socially-conscious cousin in the work of Sophie Calle, whose large-scale photo and text panels document her self-consciously ‘private-and-public’ activities. The work here, from her Biographical Stories series, gives us a matter-of-fact view onto one significant aspect (object, place, etc.) of her self-consciously documented courtship of, marriage to, and subsequent divorce from, a chance acquaintance. And The Manhattan Project, a collaborative effort by New York-based artists Janet Chohen, Jon Ippolito, and Keith Frank, suggests a politically-sensitive analog to the group’s series of absurdist projectile-and-target games. Realized in drawing, photography, text, and — ultimately — in a soon-to-be-published book, the work develops a complex matrix of indices that trace the accumulation of the ‘moves’ and activities defining each game.

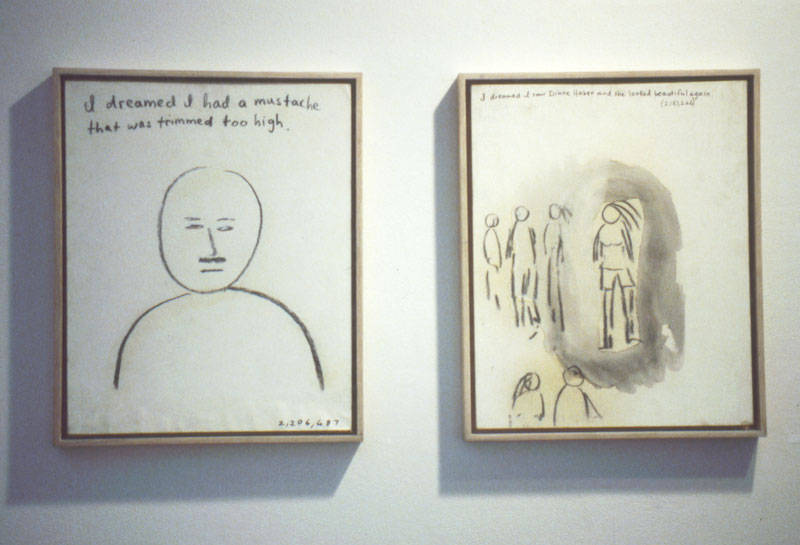

Such deployment offers a ‘maximalist’ alternative countered historically by the zen-like simplicity of the work of two seminal sixties artists: Vito Acconci, whose early seventies investigations of photography and text descriptions of ordinary, mundane movements (“Lean, click”) refer not so much to geographic sites as to the site of activity itself; and Jonathan Borofsky, whose dream drawings on canvas–from the same period–invite the viewer into the strange, childlike automatism of the artist’s dreams and, seemingly, of the open-ended but flatfooted nature of dreaming.

Closer in spirit to process-based art and Smithson’s minimalist neighbors, sun drawings by Roger Ackling record the strength of sun’s rays on particular days, as the artist directs those rays through a loupe and onto paper. Here the works’ physical beauty, and likewise that of the pebbles, text, and glass vitrine of Ann Hamilton’s work and the repetitive gestures of Massimo Antonaci’s pieces, assumes the role of ‘re-presentative,’ drawing a view from, but never relinquishing their roots in, the specificity or necessity of the activities to which they refer. And in fact only in the beauty of these works, as in that of the collective memory of In Pursuit of Lost Time — as in themadeleine’s tast — lies the desire in which such complex thought experience is contained and released.

Two piece work- one charcoal on paper and one black and white photograph

42 x 58 x 27 x 20 inches (10815.3 x 6908.8 cm)

(Inventory #7957)

Two piece work- one charcoal on paper and one black and white photograph

42 x 58 x 27 x 20 inches (10815.3 x 6908.8 cm)

(Inventory #7957)

Edition of 3

6 x 8 1/2 inches each

This installation size: 34 x 75 inches

Edition of 3

6 x 8 1/2 inches each

This installation size: 34 x 75 inches

No results found.