“My intention is to change the work of art’s function for the viewer. Art would go from being a record of someone else’s perception to becoming the recognition of your own.”

—Mel Bochner

“To observe is not the same thing as to look at or to view. “Look at this color and say what it reminds you of.” If the color changes you are no longer looking at the one I meant. One observes in order to see what one would not see if one did not observe.”

—Ludwig Wittgenstein, section III-326 from “Remarks on Color”

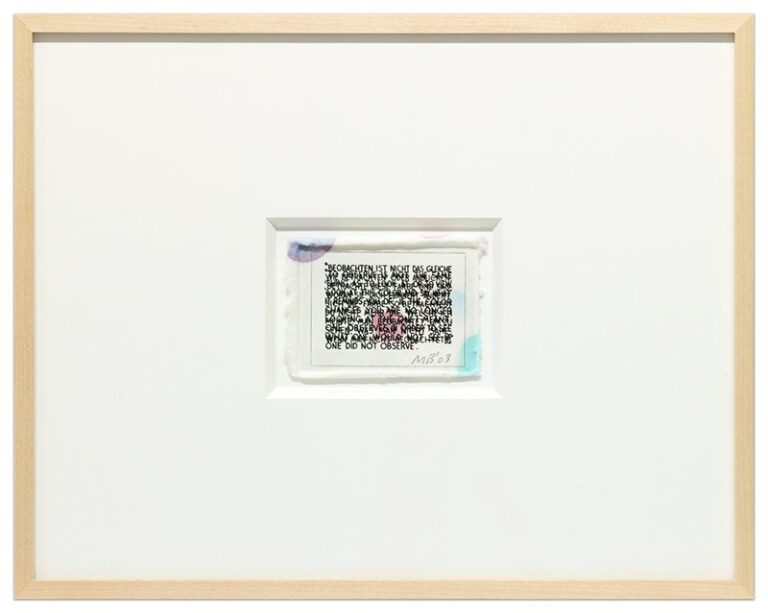

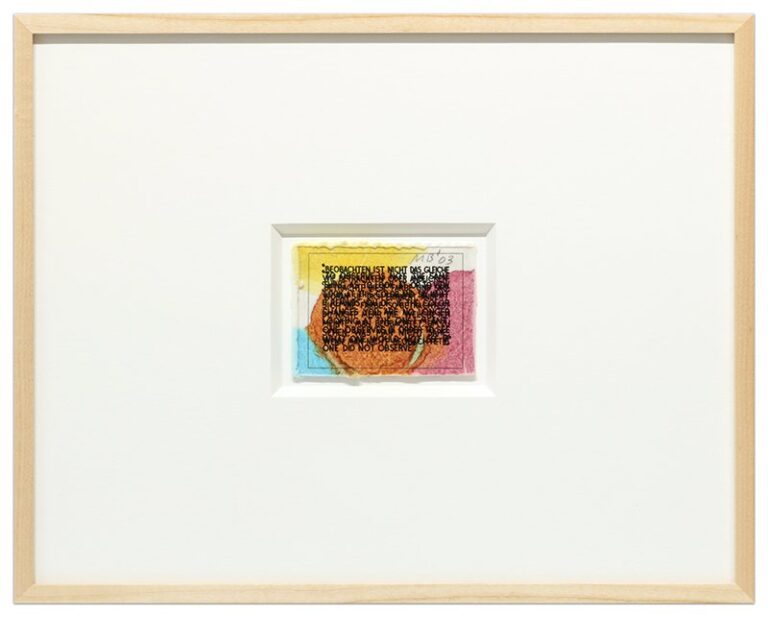

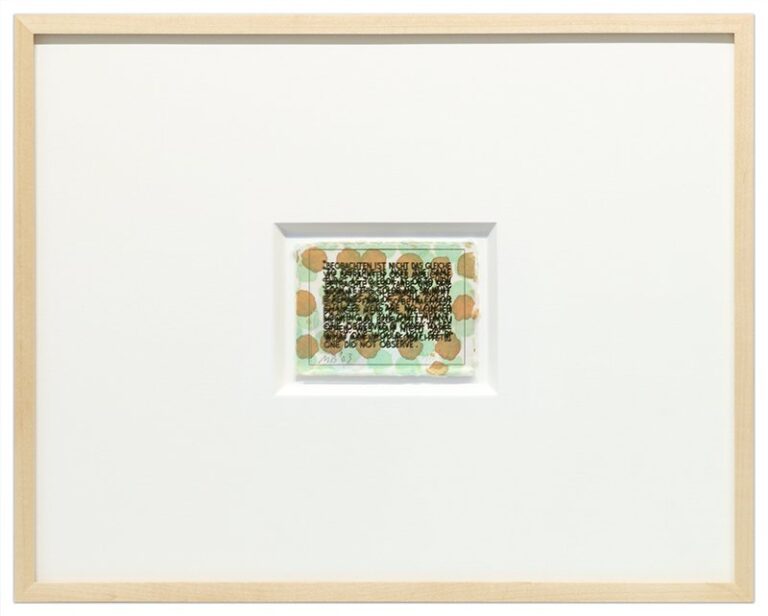

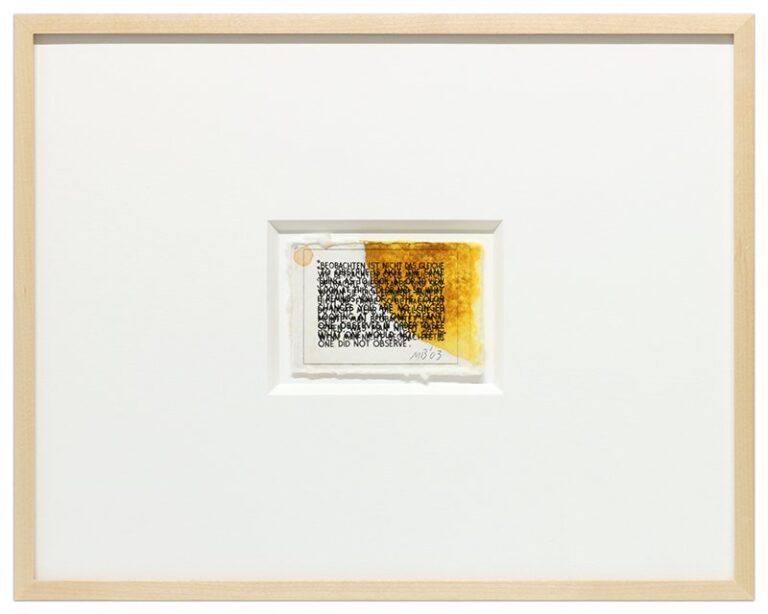

In the 2003 series, “If the Color Changes,” Mel Bochner superimposed a text, both in the German original and in an English translation from Ludwig Wittgenstein’s “Remarks on Colour” on top of an ever-varying painted background. The doubling of the text works as a palimpsest, redaction, shadow and translation all at once. The painted background further reduces the text’s clarity, accentuating Wittgenstein’s questioning of language’s ability to convey what we see. Like his iconic early 1970’s work, Bochner shows that “language is not transparent”. In 2007, Bochner described his “If the Color Changes” project:

While reading through “Remarks on Color,” I came across one of Wittgenstein’s rare self-reflexive comments. Fascinated by its opacity, and the ambiguity of its shifting referent, I decided to make a painting of it. This series, collectively titled “If the Color Changes,” deals with the conflict between color-as-experience versus color-as-grammar. The opticality of the work’s color is intended to throw one’s eye and mind out of sync, slowing reading down, making you work to extract the meaning from the text. However, the longer you think about this text the more elusive the meaning becomes. When he says ‘if the color changes you are no longer looking at the one I meant’, the ground is suddenly pulled out from under you. How did the color change? Who, or what was the agent? Was the change perceptual or grammatical?

An underlying theme of these works is the question of translation, not only from one language to another, but also from the verbal to the visual. I juxtapose the German and English texts to create a slippage between the texts, a space in which to problematize reading. What is the difference between looking at a painting and reading it? The color diverts the text from its duty to meaning, collapsing the mental space between reading and seeing. But color also creates a visual meaning, one that survives the consumption of the narrative. It has always been important to me that the visual and material aspects of my work continue to engage the viewer even after they think they have ‘gotten the idea’.