“What is it we want from art that our belief in ‘content’ works to hide from us?”

– Allan McCollum

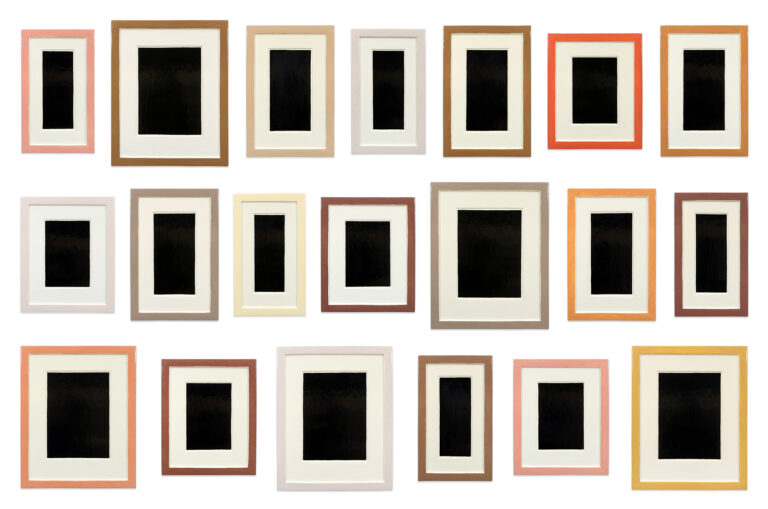

Allan McCollum’s “Collection of Twenty Plaster Surrogates” is a collection of cast objects, each painted to simulate a frame, a mat, and, where the picture would be, a black rectangle. They are clustered in the dense display style of a nineteenth-century salon. Each and every Surrogate is signed, dated, and notated. No two surrogates are identical; all those of the same dimensions have slightly different colored borders and vice versa.

Discussing the Plaster Surrogates in a 1985 interview, McCollum described his practice as, “In a sense, I’m doing just the minimum that is required of an artist and no more.”

To produce this work, McCollum and his assistants engaged in repetitive and communal labor. To a degree, he transformed the artist’s studio into an assembly line and a workshop and systematized the artistic process into stages of production: create molds, cast plaster, and the application of enamel paint to create a smooth surface. Although the panels were all executed in this way, no two panels share the same dimensions and frame color. Handmade but standardized, “Collection of Twenty Plaster Surrogates” integrates art and mass production. McCollum asks viewers to rethink conventional distinctions between types of labor and to take into consideration the human effort embedded in all objects, artistic and otherwise.

“After mounting a few exhibitions I learned quickly that the Surrogates worked to their best effect when they came across as props—like stage props—which pointed to a much larger melodrama than could ever exist merely within the paintings themselves. The Surrogates, via their reduced attributes and their relentless sameness, started working to render the gallery into a quasi-theatrical space which seemed to ‘stand for’ a gallery; and by extension, this rendered me into a sort of caricature of an artist, and the viewers became performers and so forth. In trying to objectify the conventions of art production, I theatricalized the whole situation…”

McCollum, then, produces a surrogate of painting, an empty signifier that stands “in the place of social relations, objectifying them in a displaced way,” as George Baker has astutely put it. Trevor Starke writes, “The surrogate fulfills the task of painting: it facilitates aesthetic engagement and economic exchange, produces discourse, and takes up space on the wall. It does all the things that a painting should do. But it is not a painting. It is a fraud, a fake, a stand-in.”