Walking into Stephen Prina’s exhibition with Barbara Krakow Gallery, window blinds hang from the ceiling. On the left, three have been painted on the side facing the viewer. The painting is done with a consistent gesture that leads to the assumption it was done by someone right-handed. In addition, the painting only seems to go a little above the height of most people (Prina painted only as high as he could reach without aid). On the right side when entering the gallery, two blinds hang and, because of light descending from the clerestory windows onto and through the blinds, one can see that there is painting on the side facing away from the viewer. The beginning experience of viewing Prina’s exhibition “The Way He Always Wanted It” is on both the inside and the outside (on account of the directions of the shades). The viewer is inside a building and inside the gallery. By Prina ‘collaborating’ with the architecture, no matter where one stands in the exhibition, work does and does not face the viewer (either by being hidden behind blinds or by being turned in another direction).

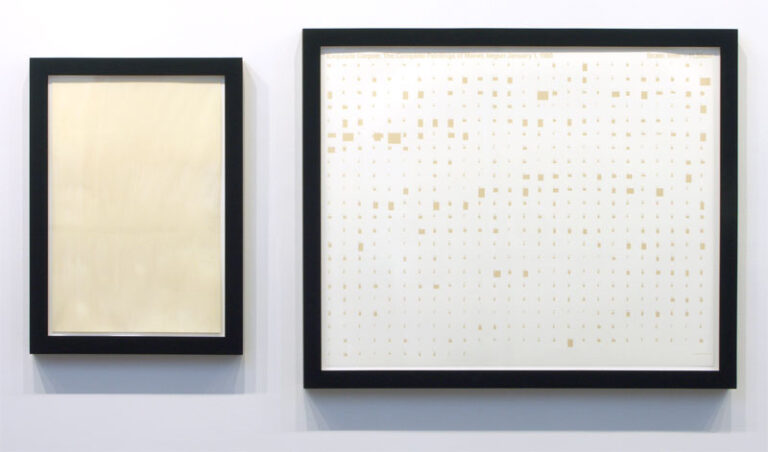

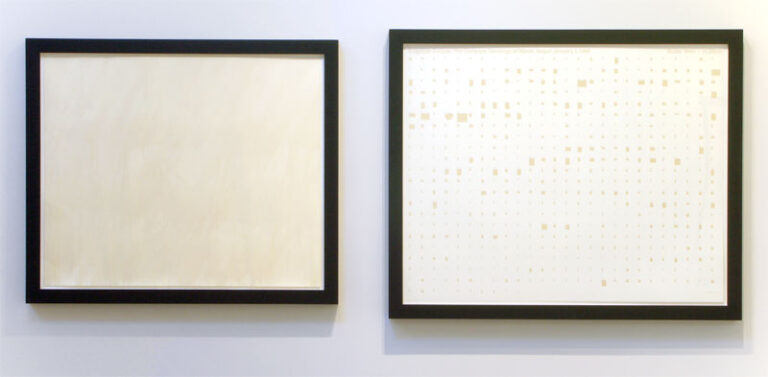

Continuing through the exhibition, just beyond the triptych of blinds on the left, is a series of three diptychs (are you getting a sense that math, equations and relationships are key to Prina’s work?!). Two framed pieces of paper comprise each diptych. The right piece of paper in each diptych graphically lays out the relative size and shape of each of the 556 paintings that Edouard Manet painted over the course of his life. The small monochrome shapes are proportional to the sizes of Manet’s actual paintings. The piece of paper on the left is a gestural ink wash (almost identical movement is visible in the gesture as in the gesture in the shade paintings) on paper that is the exact size of the Manet painting it references. The references also include the accurate title of the related painting and that the order in which the paintings have been created are the same for Prina’s as it was for Manet’s. When looking directly as these diptychs, a somewhat mysterious system seems apparent, whether because of the chart-like piece on the right, or the pairing via identical frames of the companion pieces of paper. In addition, the title, “Exquisite Corpse: The Complete Paintings of Manet, begun January 1, 1988”, the “Scale: 1mm=11.39cm” and then the ownership of the image: “© Copyright 1988 Stephen Prina” are all presented as facts. On the reception counter is the checklist referencing each piece in the exhibition, which in these pieces’ situation, includes the titles of the actual Manet paintings being referenced (more facts, but fully invisible if just looking at what’s on the wall). With all of this information, one can accept the reality of the project or extend beyond and imagine the Manet painting and the entire body of Manet’s work. One can also question the validity of the information – which because of Prina’s 1960’s Manet catalogue raisonne, is in fact, outdated and no longer fully accurate.

Moving on to the right from the Exquisite Corpse works, passing the diptych of blinds, Stephen has placed a pinkish rug that can be read as the shape of a piano and the size of a baby grand in the gallery’s ‘alcove’ . It sits on the ground like a rug should. On the postcard for the exhibition, the rug is barely visible but is used to sit on top of a baby grand piano as prop, functional protection and as artwork. In addition, an all-chrome tricked-out BMX bicycle sits on the rug on the piano. In this installation, though, it is a rug, a previously used one to be exact and in this context it is now thoroughly ‘art’.

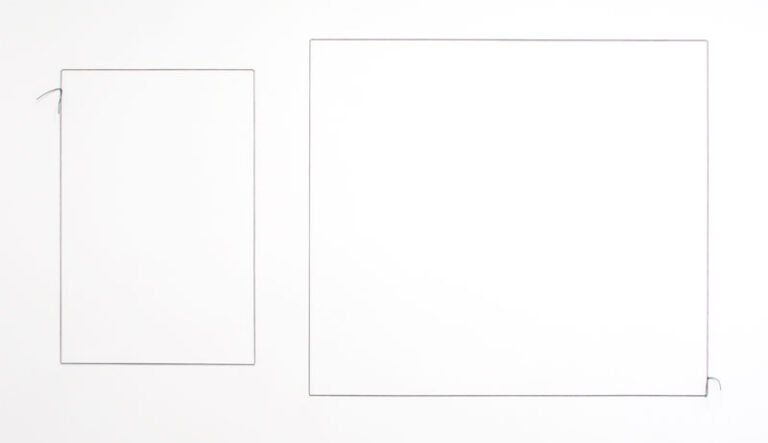

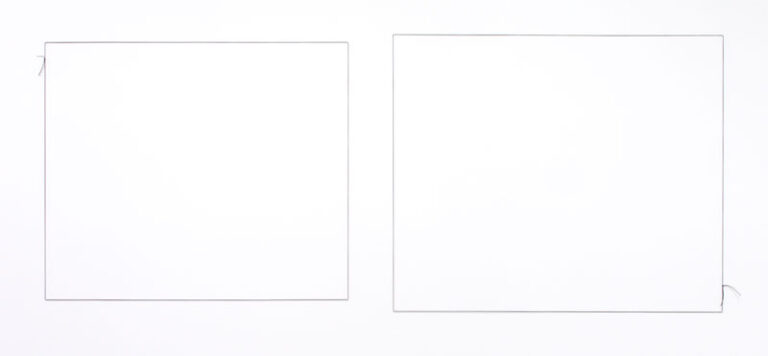

On the walls surrounding the rug in the alcove, three untitled/Exquisite Corpse works hang. They consist of cord wrapped around brass plated nails used to outline the sizes and shapes of the six panels of the three Exquisite Corpse works previously discussed. At first glance, the ’empty rectangles’ are merely that, but in one’s mind, there has to be a vague memory of what was just seen, and in fact because of how Prina installed the show, there is no way to view these works before viewing the Exquisite Corpse,so that the works cause a required use of short-term memory, yet nothing remains. The question becomes, “What is important to remember and what purpose does memory serve?”

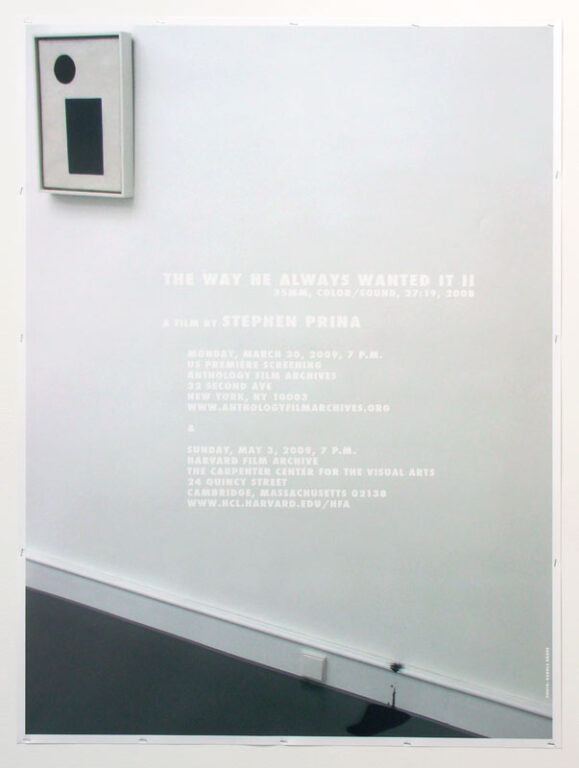

On the slanted wall to near the diptych, a photograph serves as a poster announcing the times and locations of the screenings of Prina’s recent film The Way He Always Wanted It II. The poster, itself, has no image directly coming from the film, but ‘beneath’ the text is a photograph from the Staatliche Kunsthalle in Baden-Baden showcasing a wall with a small Kazemir Malevich painting hanging towards the upper left of the picture plane and in the bottom right of the picture plane is what looks like a paint or ink stain. It is the remnants of the creation of a work in situ for Prina’s show that preceded the show with Malevich. The panel upon which the paint was sprayed is gone, but the remnants remain (the curator has actually declared that she never wants that spot cleaned!).

To further add both a sense of connection and disconnect, the film The Way He Always Wanted It II is the last piece on the exhibition checklist. Fully referenced in the gallery space on the checklist, on the poster and through a variant as the title of the show, yet it is only viewable elsewhere.

What do all these pieces with intertwined meanings and overt information, along with opaque, transparent and subtle references actually say? One can feel on the outside and not understand, or one can look and see an incomplete amount of information – some factual, some outdated, some mere clues, some presented outright, some through remnants and some obfuscated. Much like daily life, one asks many questions: How to make sense without all the information? How to feel comfortable being on the outside? When is one actually on the outside? Is the feeling of being included/excluded more an internal feeling or is it caused by outside forces? If a work can be enjoyed visually, does there need to be full understanding? Does there need to be meaning? What is meaning? Each of the individual works and the exhibition as a whole engage this issue of inclusion/exclusion.

Opening Reception: April 18, 2009, 3-5 P.M.

In conjunction:

7 P.M., Sunday, 3 May, 2009

Harvard Film Archive

will screen Prina’s two most recent films:

” THE WAY HE ALWAYS WANTED IT II ” (2008, 35 mm, 27:19)

” VINYL II ” (2000, 16 mm, 21:30)

Stephen Prina will be present to discuss the films

Harvard Film Archive,

24 Quincy Street, Cambridge

(617) 495-4700

http://hcl.harvard.edu/hfa